A slow and bumpy journey on the trail of Africa's copper.

Congo's copper output has tripled over the past decade, and there's more to come. Videographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

In order to get a truckload of copper out of Africa and into the hands of tech-hungry buyers, Chanda Kulungika must spend a week sitting in one of the world's longest traffic jams.

Young men weave through the 30-mile (about 50 kilometers) queue pushing crudely built bicycles stacked with soft drinks, snacks and charcoal. At night, Kulungika sleeps in the cabin of his truck with one eye open, periodically flashing his hazard lights to check for lurking thieves who might steal his fuel or the valuable minerals he's transporting.

The Long Road to Market

Routes from copper mines in Congo and Zambia to ports

Sources: Bloomberg; Google Maps

This scene on the border between Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, where the sound of idling diesel engines and the sour odor of sulfur fill the air, seems an unlikely front line for the battle against climate change.

Yet it is as important as any wind farm or electric-vehicle plant. Because, while everyone from the International Monetary Fund to Elon Musk is warning that shortages of metals like copper could hinder the energy transition, production here is actually booming: the region supplies two-thirds of the world's cobalt, and it accounted for more than 80% of global copper output growth over the past three years.

But Africa's metals are no good to anyone if they can't get out.

The 1,900-mile journey from mines in Congo and Zambia to the ports is so riddled with bottlenecks and jams that it can take more than a month.

A recent journey along the route to the coast shows how, a century after commercial mining began here, the world's hunger for copper is again reshaping the region. It also highlights the difficulties in electrifying the world: even here, one of the few places where production is growing, the logistical challenges could throttle the flow of copper and cobalt to the global market.

Trucks wait in a days-long queue to cross into Congo from Zambia. Drivers have it rough. There are no toilets, lodges or running water while they wait in the scorching central African sun.

Photographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

Informal traders carry goods across the Kasumbalesa border. At the main trading point into southern Congo, the lorries connecting the mines to ports jostle with trucks, buses and young men ferrying goods on reinforced bicycles.

A truck driver prepares a roadside meal while waiting to cross the Congo-Zambia border. Videographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

Many drivers carry small stoves called 'mbaulas' and buy bags of charcoal to fuel them along the journey. Photographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

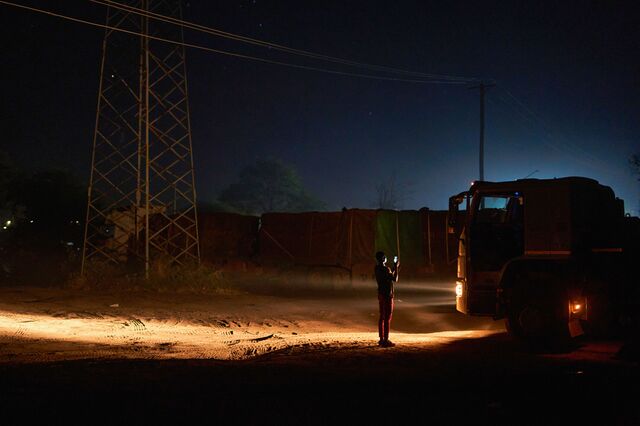

A driver makes a video call at a truck stop just outside the Kazungula border. It's a long and lonely journey — truckers say social media helps when they're forced to spend weeks away from home at a time.

Photographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

The road through Congo and Zambia often looks more like the surface of the moon than a highway. Stretches of tarmac are missing, and the dirt gets churned into a quagmire during the rainy season. Where the paving remains, truck tires have carved deep ridges into the tar.

The journey for truckers like Kulungika begins a couple of hundred miles from the Kasumbalesa border post in the heart of the Central African Copperbelt, a rich mining tract which stretches from southern Congo into northern Zambia.

It's a region that many big international miners avoided for years, but now production is booming just as other key mining countries fall short.

Congo's copper output has tripled over the past decade, and there's more to come, from companies including billionaire Robert Friedland's Ivanhoe Mines Ltd., which just opened the vast Kamoa-Kakula complex of mines, commodities giant Glencore Plc and China's CMOC Group Ltd. Already the world's largest cobalt producer, Congo is set to increase production by 79% by 2025 compared to 2020, according to Darton Commodities Ltd.

Zambia, too, has ambitious expansion plans. The region could add nearly 1 million tons of annual copper production over the next decade, according to Adam Khan, copper supply analyst at CRU Group, and others are more optimistic still.

"Copper is the new oil," Zambian Finance Minister Situmbeko Musokotwane said in an interview. "This is a very good opportunity for us."

There's no doubt that the region's copper will be needed. To meet the global target of net-zero by 2050, the world may need to double supplies of what S&P Global calls "the metal of electrification." "The green-energy transition is the biggest purchase order in history for the commodities industry," said Benedikt Sobotka, chief executive officer of miner Eurasian Resources Group.

To be sure, logistics are not the only impediment. Corruption is rife, and disputes with governments are common. One of the largest copper and cobalt mines, Tenke Fungurume, hasn't been allowed to export any material since July because of a dispute between its owner CMOC Group and Congolese state mining company Gecamines.

Other operations present technical difficulties. Mufulira, in Zambia's Copperbelt province, is one of the world's oldest producing copper mines, and must pump out enough water to fill 47 Olympic-sized swimming pools every day, or risk flooding.

Mufulira is part of Mopani Copper Mines Plc, which Glencore sold to Zambia's state-controlled investment company last year.

The mine must pump out enough water to fill about 47 Olympic-sized swimming pools every day, or risk flooding.

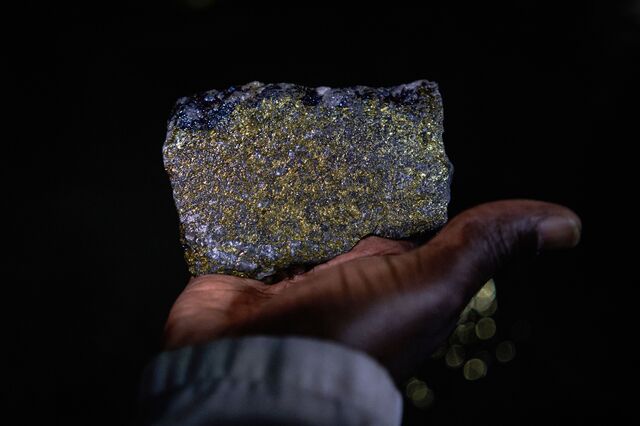

A chunk of copper ore blasted from the underground rockface, containing more than 2% of the metal.

The Henderson shaft that reaches more than 1,500 meters below surface in Mufulira is one of Mopani Copper Mines' newest.

The ore is crushed, processed and refined into plates called cathodes that are 99.99% pure.

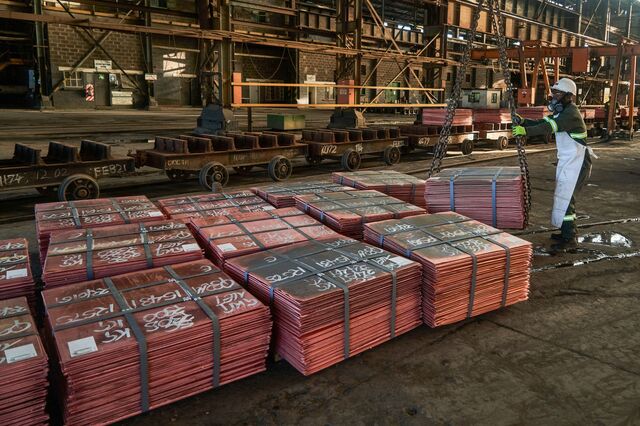

Plates of finished copper ready for the journey to the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania for export.

Miners at Mufulira. Mopani provides more than 10,000 jobs, making it one of Zambia's biggest employers.

Photographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

On the surface, the ore is crushed, processed and refined into plates called cathodes that are 99.99% pure. From there, they are loaded onto trucks and join the bumpy journey to the coast, and the global market.

Along the highways, the sour smell of sulfur used to extract copper wafts through the air as lorries roll by. The traffic is busy in both directions: while metal heads south, mine operators must truck in everything from food and diesel to giant slabs of steel.

"There used to be no queue like this," said Wisdom Chabu, who was transporting acid – used to extract metal from raw ore - at the border. "We are failing to cope."

It can take as long as two weeks just to get out of Congo and into Zambia, when the queue stretches to 30 miles, as it did around mid-year. Eight days is considered a good time, according to one big mining company. All told, when Bloomberg traveled stretches of the route between May and July this year, it was taking as long as 35 days to get from a mine in southern Congo to southern African ports.

In October, the queues flared out again after drivers demanding improved security on Congo's highways refused to enter the country. It took a call from Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema to his counterpart in Congo pushing for better conditions, before drivers agreed to resume.

Costs have also rocketed: rates for trucking a ton of copper from Congo were this year almost double those in early 2021. Shipping rates rose sharply too.

At Livingstone, about 600 miles south of Kasumbalesa, the road divides. Some drivers head to Zimbabwe via the historic Victoria Falls bridge built more than a century ago as part of Cecil Rhodes's colonial dream of a Cape-to-Cairo railroad.

Others go to Botswana, which since last year has been connected to Zambia by a shiny new bridge.

The 1,900-mile journey from mines in Congo and Zambia to the ports is so riddled with bottlenecks and jams that it can take more than a month.

A giraffe on the road as the highway passes through Zambia's Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park, a few miles upstream from the Victoria Falls world heritage site.

The Victoria Falls bridge linking Zambia and Zimbabwe was completed in 1905, and can only support one truck crossing at a time.

A Zambian traffic policeman patrols in Kasumbalesa.

The road through Congo and Zambia often looks more like the surface of the moon than a highway. Stretches of tarmac are missing.

A border worker directs trucks at the Kasumbalesa border. While this is where the worst logjams are found, the problem is pervasive across the route.

Photographer: Zinyange Auntony/Bloomberg

On the other side of the Zambezi River, in both Botswana and Zimbabwe, drivers dodge donkeys and cattle along potholed roads.

They're about to start the most dangerous stretch of the journey. In South Africa, truck hijackings jumped by a third in the first three months of the year, according to official crime statistics. Police don't say how many of these are copper trucks, but metals make for lucrative targets: a cargo could be worth about $340,000 at the record prices touched this year.

The business has become so dangerous that most logistics companies only allow their drivers to move in a convoy with an armed security escort through South Africa. Thieves have even started targeting cobalt hydroxide cargoes, according to one producer that's had six trucks robbed since last year.

Truckers also have to deal with frequent violent protests along South Africa's highways. Insurance costs have rocketed as a result.

Once they reach Durban, one of Africa's busiest ports, the drivers' job is over. But the logistical problems are not.

The port is still recovering from some of the worst floods on record that struck in April, causing severe damage. Even before that, Durban ranked as one of the least efficient container ports in the world in a World Bank study in 2020.

Last year, as the aftershock of the Covid pandemic disrupted container shipping globally, traders circulated photos of copper cathodes stacked in car parks after long delays to load material meant that the city's warehouses were all full. Some miners started using bulk carriers, rather than container ships, to transport their metals.

Durban port is still recovering from some of the worst floods on record that struck in April, causing severe damage. Even before that, it was ranked as one of the least efficient container ports in the world. Photographer: Guillem Sartorio/Bloomberg

For copper miners and traders, the ballooning delays are a constant headache. Many are increasingly using alternative routes to countries like Namibia, Tanzania and Mozambique, trying to avoid the queues and dangers of the route to South Africa. Transporters estimate that Durban once handled 70% of Central Africa's copper exports; it now accounts for about 40%.

The governments of Congo and Zambia are trying to address the problem. In June, they agreed to open the border posts between the two countries 24 hours a day, although there has been no clarity on when that might actually happen.

For the truck drivers who ply the route, the delays, dangers and corruption add up to a constant source of stress.

"Truck drivers have suffered a lot in this situation," said Josiphat Phiri, who has been driving the route since 2000. "It's very difficult now to transport copper. On the South African side, there's too much hijacking, too much killing. You can only breathe fresh air after you're offloading. As long as you have copper on a trailer, you know that things are not safe."—With Taonga Clifford Mitimingi, Mark Burton, Michael J. Kavanagh, Paul Richardson and Jeremy Diamond